There has been some great chatter about the end of “blurbs,” those little endorsements on the backs of books that are supposed to entice us to read the books. Before I delve into this matter further, I’ll give you my bottom line: unlike a lot of authors, I like blurbs as a concept, and unlike a lot of readers, I use blurbs to help me decide what to read.

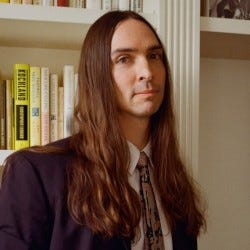

But let’s back up, for those of you who don’t follow publishing, those of you to whom “Binky Urban” sounds like a line of streetwear lingerie or a next-gen real estate agency. Last week, Simon & Schuster editor Sean Manning—whose hair we must pause to inspect, and respect—

—for he has the best male publishing hair since Morgan Entrekin in his heyday—

—wrote an essay in Publishers Weekly abjuring the use of blurbs. He wrote:

Since becoming publisher of the Simon & Schuster flagship imprint a few months ago, I’ve been spending a lot of time researching old titles we’ve published to get a better sense of our history. There have been many surprises: a 1925 poker handbook that came with chips hidden in an ingenious rear-binding compartment; fourteen-year-old actress Elizabeth Taylor’s memoir about her pet chipmunk Nibbles; 1960s anonymous tell-alls about alcoholism and going bust in the stock market…

Most surprising of all, though, has been discovering how many of the biggest-selling, prize-winning and most artistically revered titles in the flagship’s history did not use blurbs for their first printings: Psycho, Catch-22, All the President’s Men, Looking for Mr. Goodbar (also published in 1975…the flagship certainly embraced the sexual revolution!), Where Are the Children?, Norwood, The White Album, Lonesome Dove, No Ordinary Time, Parting the Waters, John Adams, and Steve Jobs, to name just a few.

This got me thinking about the practice of blurbs….

In no other artistic industry is this common. How often does a blurb from a filmmaker appear on another filmmaker’s movie poster? A blurb from a musician on another musician’s album cover? A blurb from a game designer on another designer’s game box? The argument has always been that this is what makes the book business so special: the collegiality of authors and their willingness to support one another. I disagree. I believe the insistence on blurbs has become incredibly damaging to what should be our industry’s ultimate goal: producing books of the highest possible quality.

On the scent, The New York Times ran a follow-up in which it examined the premise, asking if blurbs really do move books. They land on no:

Here’s a sad truth, given how much effort goes into blurbs: They might not be that important to the average reader.

On a Sunday, 18 out of 20 readers asked in an informal survey at Indigo, a bookstore in Short Hills, N.J., had no idea what a blurb is.

When asked whether she selects books based on adulatory praise on the jacket, Jaclyn Tepedino, 29, said: “Me, personally, I do not. I’m looking at the summary.”

Sylvia Costlow, 86, said that praise from David Baldacci or Daniel Silva would catch her eye; otherwise, she forms her own opinions. Her daughter, Elaine Graef, 59, agreed: “I shop a lot online and pay attention to what other readers say about a book.”

Charles Han, 24, and Joanna Baltazar, 23, were browsing in the fantasy section when they learned the proper term for quotes on the front of books. Do they pay attention to these quotes? “No,” Baltazar said. “Never,” Han agreed.

Kevin Miller, a 67-year-old “Star Trek” fan, said he would take note only if William Shatner endorsed a book.

Well, this is a bucket of cold water. Over five books, I have spent a lot of time asking friends and strangers alike in the author community to give me blurbs (thank you to all who have!), and I have paid it forward for at least a dozen other authors. Does it matter? Maybe not.

But actually … maybe it does.

I’ll get back to the blurb question in a moment. But let’s take a break for a moment for some other, fun business.

I recently promised that I would collab with ChatGPT to produce dead-on portraits of new paid subscribers. A bunch of you are in the queue, but we are going to start with David G., whom I described (based on no evidence except my very keen intuition, crop circles, an astrological chart, and a very vivid dream) this way: “a 27-year-old named David who loves Ali G and the Beastie Boys, reads a lot of Joseph Heller, dresses in basketball jerseys, and eats ramen.” And ChatGPT rendered him thus:

Do I know why ChatGPT created a poster featuring the names “Beastie Boys” and “Joseph Heller” but with a picture of neither? I sure don’t! But the ramen is dead-on. My mouth is watering. Also, dig the boom box above the boxy old-school TV.

Okay, back to why blurbs may sometimes work, and be a good thing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Oppenheimer to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.