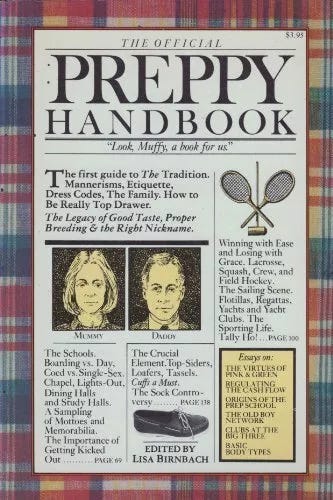

Given my longstanding interest in all things prep—which, in my day, has landed me assignments like reviewing the inadequate updated edition of the classic Preppy Handbook, now behind a paywall at the degraded Slate site—it is surprising, to me anyway, that I have not adorned this newsletter with more prepitude. You know, like this:

But, thanks be to Muffy, I have two prep items for your consumption.

First, on a recent road trip with my eldest daughter, we curled up in front of the laptop at our hotel and feasted our eyes on The Holdovers, another brilliant movie from director Alexander Payne. Between Election and The Holdovers, Payne has now given us the two great indelible portraits of high school life in the new millennium, the former being about public schools, the latter about prep schools. (I think we need a movie from him about Catholic schools.) I don’t have a full review of The Holdovers; let me just say that it’s especially good at upsetting the prep-school stereotypes, in which the boys are all white, rich, and adept at rowing, and in their place giving us the cramped, often uncomfortable world of real boarding schools. In real life, boarding schools are a lot like real world, only at closer quarters, and with different dress codes. They are a lot like the army, in fact—with hierarchies, codes, and slow-changing traditions; and with the potential for real unity and esprit de corps, as well as for abuse and alienation. Also, The Holdovers has Paul Giamatti, and the best neo-1970s title cards since the 1970s themselves. Credit to designer Nate Carlson.

For deeper thoughts on the movie, shot at Deerfield Academy and several other prep schools, I will defer to my old schoolmate Wesley Morris, who now has at least three distinctions that I can think of:

• He wrote the best piece ever on the mustache.

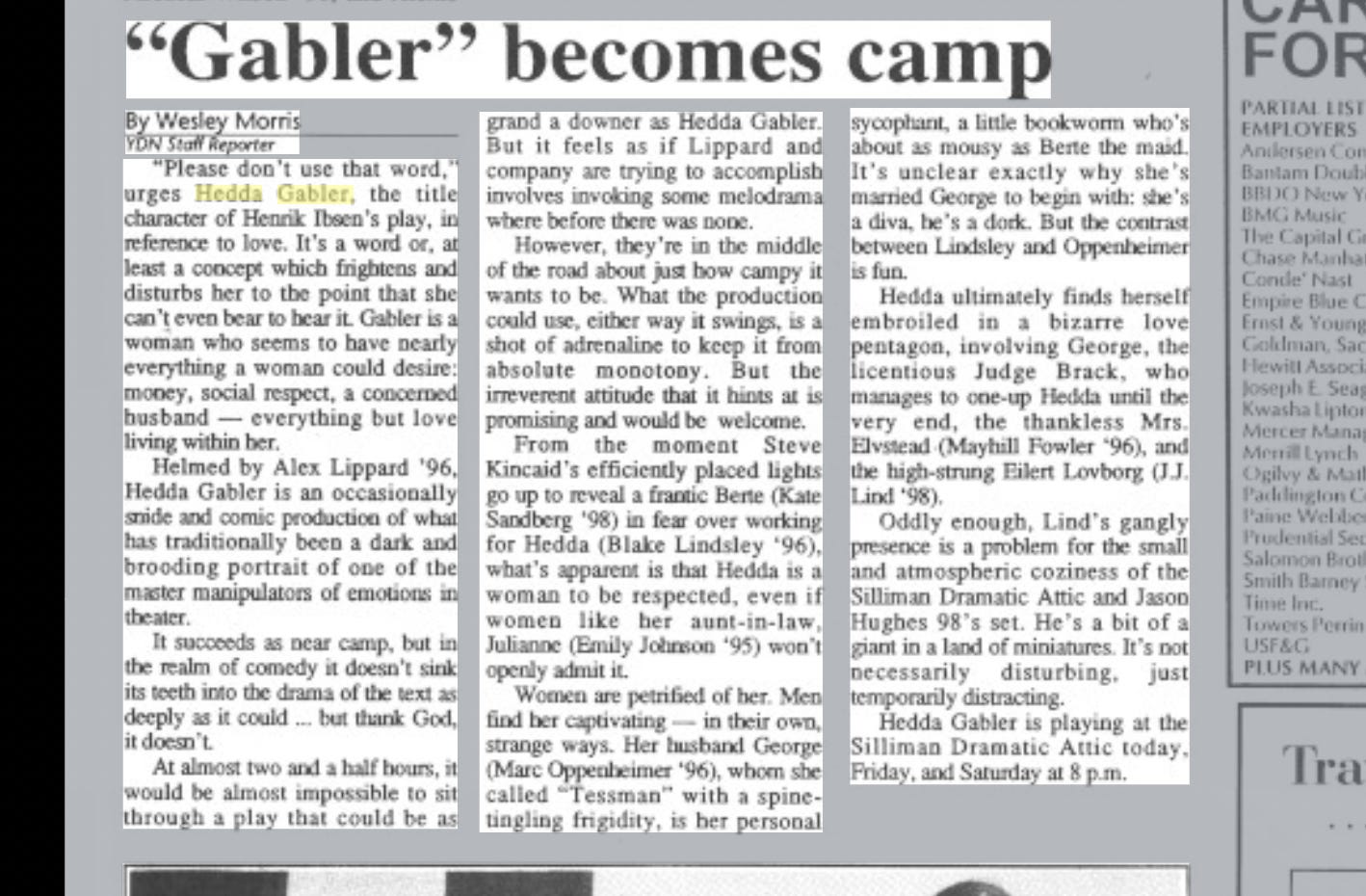

• He was the last critic ever to review my acting—he covered a 1994 student production of Hedda Gabler in which I played Tesman. Here’s the review:

• He used his review of The Holdovers to draw a brilliant comparison between director Payne and another contemporary auteur, Wes Anderson:

Once it’s all over, and the movie has reminded you of “Dead Poets Society” or maybe half a dozen films from the 1970s, like “The Paper Chase,” you might also feel what I did: like you’ve seen an inversion of Wes Anderson’s “Rushmore,” which opened 25 years ago. Payne and Anderson arrived at roughly the same moment in the mid-1990s. Only, Payne’s milieu is world-weary, harsh, slouched, bluer-collared, grayer. I saw “Rushmore” when I was loosely older than Max Fischer, the movie’s go-getting, adolescent old-soul protagonist. Anderson’s declarative archness and rigorous eye rocked my world. A geek had gotten his revenge, opening a nerdcore floodgate. But, more important, his romanticism felt true. Cruelly, my peer is now Paul Hunham, a figure humbled by principle, hampered by pride and, by the end of “The Holdovers,” humbled some more; he’s Max Fischer, slumped.

Watching Anderson’s films has steadily made me the ogler Matthew McConaughey plays in “Dazed and Confused”; I keep getting older, and they just stay the same. The romanticism has calcified; his movies are less ardent, as much sculptures to passion as passionate themselves. Payne’s weakness was for pessimism, a hardened freewheeling version. His movies were about cynics, the native-born and the arrivistes. But somewhere along the way, he and Anderson swapped and the romantic intruded. Payne’s characters began needing each other and connecting, and that crackle kicked in. That’s especially true of his last two — the other is “Downsizing,” a soulful futurist satire with Matt Damon and Hong Chau that nobody saw. In middle age, Payne has come newly to life, whereas the Anderson of 2021’s “The French Dispatch” and this year’s “Asteroid City” seems to me as alienated from sensation as ever, hiding in and fussing over the past rather than interrogating or inhabiting it.

Extra points for the Wooterson reference. Well done, Wesley.

The best prep-school academic treatise ever?

That’s what my brother seems to think anyway. In a shameless fraternal Substack cross-posting, I highly suggest you read Daniel J. Oppenheimer’s essay on a book about St. Paul’s School. A bit of it now, for your pleasure:

In the fall of 1993 Shamus Rahman Khan, now a professor of sociology at Princeton, arrived as a freshman at St. Paul’s School in Concord, New Hampshire. The American-born son of immigrants from Ireland and Pakistan, Khan was a modest outlier at St. Paul’s. He’d grown up with money—Dad was a successful surgeon—but it was suburban professional money, and the family’s cultural capital was of the typical immigrant striver sort. They drove nice cars, ate at nice restaurants, lived in a nice house in a nice suburb of Boston. Shamus was a fully assimilated child of the American upper middle class, in other words, but he wasn’t native to a place like St. Paul’s, one of the wealthiest and most exclusive boarding schools in the United States, one of a select few New England prep schools—along with places like Groton, Andover, Exeter, and Deerfield—organized to educate those in possession not just of affluence but of the kind of social, cultural, and political capital that is able to shape and direct American systems of privilege and power.

Years later, Khan returned as a teacher at SPS, and a researcher working on a dissertation. Among his findings was that the old to-the-manner-born mores taught to SPS alumni have morphed into a new set of codes taught to their grandchildren. The new codes are basically about feeling comfortable and at ease everywhere:

What Khan means here by “privilege” overlaps with but is not identical with how the word has come to be used in the culture wars of the last decade. Having it does not mean, as “white privilege” or “male privilege” is usually taken to mean, that one moves through the world arrogantly, taking up more space than is fair, casually steamrolling the interests and voices of those with lesser privilege. It is, rather, that one with Khan’s version of privilege has acquired a set of skills and manners that allow him to move with ease in many different contexts, including those in which he’s interacting with people with less money, power, and privilege. It is not just the presumption that one belongs everywhere, but that presumption paired with the actual capacity to adapt well to an unusually broad range of environments. This could entail forthrightness and assertiveness in one context, if it’s a space where these qualities are respected and rewarded (the debate team, say). It could entail humility and deference when volunteering for a social justice group, knowing when to stay silent so that other voices can be centered. In class it might involve exhibiting just the right mix of diligence, humility and impishness. As captain of an athletic team, it could mean the exuding of a grounded authority. At a party with one’s friends it could be silliness and vulgarity

[…]

Insider knowledge is a precious currency at St. Paul’s, but you have to earn it—learning as you go, making lots of mistakes, distilling lessons from those mistakes, incrementally adapting to the hierarchies as you ascend through them. You learn how to get by, how not to embarrass yourself, how to earn the respect and affection of your teachers, how to make friends and acquire social status, how to follow, how to lead, when to quote Shakespeare, when to drop a Drake lyric, when to quote Martin Luther King, when to step forward, when to step back, when to be vulgar, when to be reverent, when to be aggressive, when to be deferential.

Read the whole thing—the essay, I mean. The book, too (I plan to).

And go swimming. We all need to swim more. I recently had a birthday party by the beach. I hired an ice cream truck. The truck came with a dog.