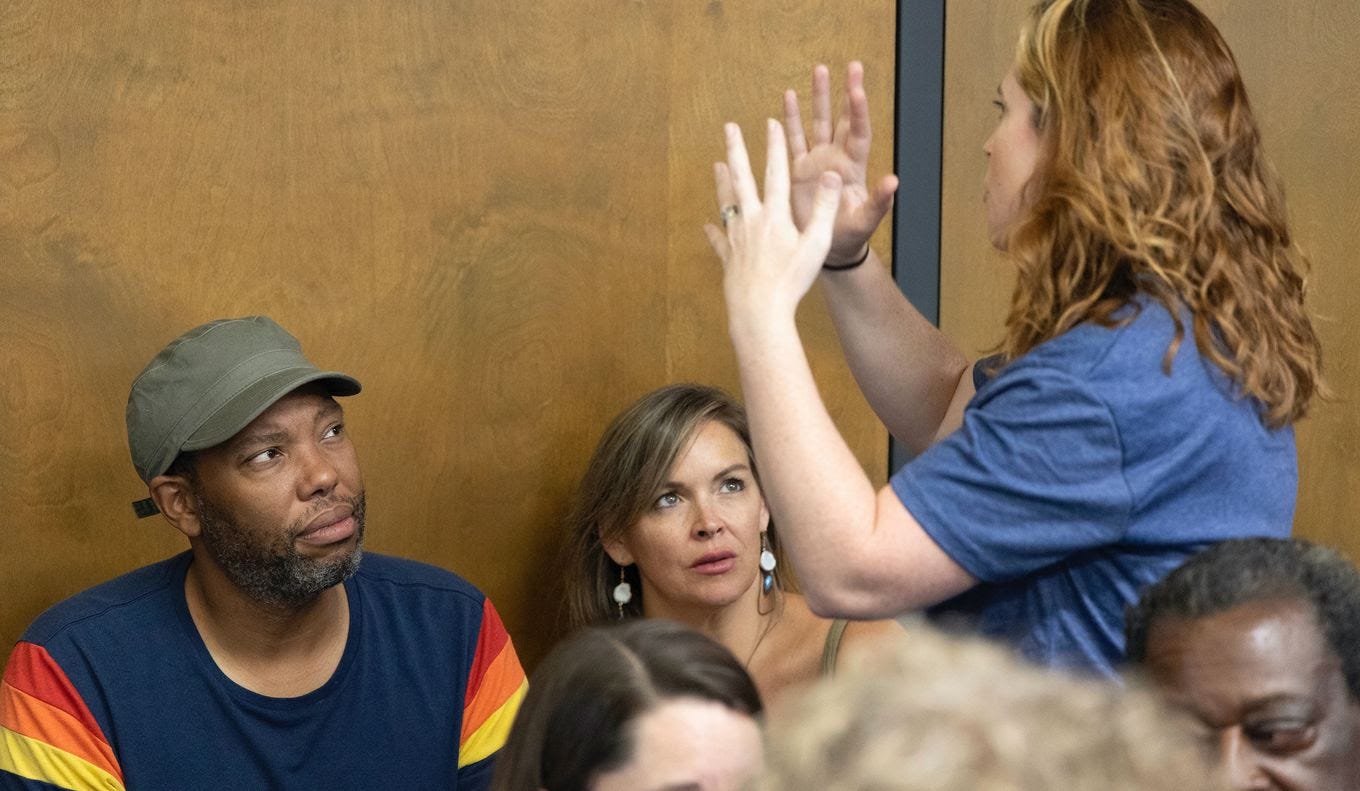

It’s summer, my posting has been a bit light, but I have a grab bag of thoughts. The first is that when Ta-Nehisi Coates showed up at a school board meeting in South Carolina to defend his book, which was being challenged, he wore a great shirt. That’s not a very profound thing to say; I have deeper thoughts, about censorship and book-banning, and you can guess at what those thoughts are, given that I am a writer and a free-speech nut. But for now, let’s appreciate the retro-’80s neo–Ocean Pacific vibe of TNC’s shirt:

For what it’s worth, I strongly suspect he is wearing Marine Layer.

Maybe theater’s problem is that it’s bad

OK, I have a saucier take for you. I read this op-ed in the Times about how American theater is dying.

The American theater is on the verge of collapse.

Here’s just a sampling of recent dire developments: The Public Theater announced this year that the Under the Radar festival, the most exciting of New York’s experimental performance incubators, would be postponed indefinitely and later announced it was laying off 19 percent of its staff. The Humana Festival of New American Plays, a vital launching pad for such great playwrights as Lynn Nottage and Will Eno over the past four decades, was canceled this year.

This season the Williamstown Theater Festival, one of our most important summer festivals, will consist of only one fully produced work, alongside an anemic offering of staged readings. The Signature Theater, whose resident playwrights have included Edward Albee, August Wilson, Tony Kushner and Annie Baker, is delaying the start of its season and, even then, will produce only three new plays rather than the customary six.

The writer, Isaac Butler, thinks that theater needs a bailout:

This is why federal intervention is required. It might seem like a radical suggestion, but in fact, it’s not even new. The Federal Theater Project, which ran from 1935 to 1939, was part of the New Deal effort to fund artistic endeavors. The project sparked an explosion in theatrical activity and inspired a generation of theater makers—including Arthur Miller, Elia Kazan and Orson Welles—and through its Negro Theater Project provided targeted support for Black theater artists across the country.

I was elated to find the paper of record endorsing my intuition, as a long-time theatergoer and -lover, that American theater is in bad shape. But I was annoyed that he didn’t address one possible cause, which is that theater may be sucking. I have seen a bunch of plays since COVID restrictions lifted or abated, some in New York, some in New Haven, some elsewhere, and my general reaction is that the new works that small theaters are producing are worse than they should be. The theaters themselves have become hyper-political, with trigger warnings in every program book, land acknowledgments (which, in the absence of actually giving land back to Native peoples, are preening and offensive), and condescending signage indicating how welcoming the theater is, all of which makes it harder than ever simply to get lost in the plot of the play. And the plays themselves (I’ll take the Yale Rep’s most recent season as an example) are chosen for their heavy-handed politics, rather than their quality.

But I have a bigger point, beyond mere carping. Elite theater, along with poetry, is the American art form that is least market-tested. There is no money in it; it seldom breaks even. It’s always dependent on philanthropy, donors, the largesse of rich people; if you don’t believe me, read Butler’s op-ed, which sings the praises of government support as well as the Ford Foundation, etc. This underwriting helps, and may be necessary, but it has a drawback; it allows theaters to produce stuff that people don’t necessarily want, that maybe they wouldn’t produce if they had to rely on ticket sales. I hold with the great Dave Hickey that there is no shame in thinking of artists as hustlers, day-jobbers, free lances, small businesspeople—people who have something to sell, in a marketplace. Remove the market incentive, and what you have are wealthy families and nonprofit boards granting money to theaters to make bad art that flatters their own politics.

So next year, we’re probably not re-upping our Yale Rep subscription. Rather, we’re going to see a bunch of plays at the Kweskin, a small community theater that is going to produce old warhorses like Arsenic and Old Lace, The Sound of Music, and The Mousetrap, as well as newer warhorses like The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee. We took the kids to see their production of Into the Woods two years ago, and it was magical. At the Kweskin, they make theater that people want to see.

I say this as somebody who loves theater more than I love any other art form. From the ages of ten to 18, I wanted to be an actor (then I got to college, acted alongside better actors, and realized I wasn’t very good). The most powerful experiences of art that I’ve had have been in the theater. I’ll never forget the undergrad production I saw of Angels in America, or the time I saw Brian Dennehy as Willy Loman in Death of a Salesman (I broke down sobbing at the end), or the remarkable Yiddish-language Fiddler on the Roof. Or numerous less famous shows, often done by amateur casts. Theater has an unmatched power to delight, or at least to delight me.

At the little shop down the corner

So here’s something that happened to me Friday morning.

As I was sitting in the coffee shop on my street, working on this newsletter, an old friend from the neighborhood walked in with a woman I had never seen before. They sat down and started talking about the virtues of our small neighborhood. I insinuated myself into the conversation and learned that the woman was moving to the area (from Brooklyn, of course) and was trying to decide if she should settle here or “on the Shoreline,” in one of the very wealthy towns like Madison or Guilford. She was concerned about New Haven’s schools (understandable; as a long-time New Haven Public Schools dad, I have stories), but also charmed by the warmth and scale of our Westville neighborhood.

And then, as we were talking, I was approached by my old friend Jerry (as we’ll call him), a seventy-ish character who lives in the neighborhood, volunteers for political campaigns, is active in every civics group, and can be seen taking long walks with his wife, a beloved elementary school teacher.

“Hi Jerry,” I said.

“My wife died two weeks ago,” he said.

I hadn’t known she was sick. I hadn’t known about the cancer that had recurred. I had missed the memorial service. (“A hundred and forty people came,” Jerry said. “Old students flew in from around the country.”) I gave him a hug. We chatted for a little while. Then he looked down at my laptop and said, “Well, I’ll let you get back to your work.”

I looked over at my computer, too. “Work’s not important, Jerry,” I said.

“Yeah,” he said. “I try to remember that, too.”

1,000 subscribers!

Thursday I got a note from Substack that I have 1,000 subscribers. So mazel tov to all of you for being among the founding 1,000. It is very gratifying to have this audience, many of whom followed me over from my podcast, others of whom know my books or op-eds. Please spread the word, and thank you for supporting me however you can. (I think about 100 of you are paid subscribers—who wants to be # 101? There is a link at the bottom.)

What I’m reading

My man Boone, other member of my two-man book club, has me attempting The Plague in French, which I last did in high school. (La Peste, if you will.) I am pre-reading it in English to get me started. Which I definitely didn’t do in high school. No, most certainly not. Really.

But I also have just put my money where my mouth is, re-subscribing to the New Haven Register, in print as well as online, which means I am now getting two print papers: the Register every day, and The Wall Street Journal weekend edition. I get the Times and Washington Post digital only.

And I have subscribed to County Highway, the new print-only magazine edited by my friend David Samuels. I think it is going to be a smash. The only web content is its subscription page, and I’ll quote the editors’ letter here:

Some of us fear the specter of an incipient totalitarianism emerging from our laptops and iPhones. Some of us are simply allergic to conformity and brand-names. What we share in common is a revulsion at the smugness, sterility, and shitty aesthetics of the culture being forced upon us by monopoly tech platforms and corporate media, and a desire to make something better. We encourage you to think of our publication as a kind of hand-made alternative to the undifferentiated blob of electronic “content” that you scroll through every morning, most of which is produced by robots.

The name County Highway is inspired by what we believe is the perfect-sized place for the enhancement of life and art. A county is a chunk of earth big enough to allow for a variety of human types, but small enough to get to know a decent number of your neighbors, where they come from, what they’re proud of, what they fear, what they smoke, what they drink, and what they love. Counties are the right-sized places for telling stories. Mark Twain had Calaveras County, which is a real place in California. William Faulkner had Yoknapatawpha County, a made-up place in Mississippi. Edmund Wilson had Hecate County, a seductive place in Connecticut. Philip Roth had Essex County, New Jersey.

The county where our newspaper is located is somewhere between all those places, real and imaginary. It’s the scale of the place that’s important to us, and also the idea of traveling from one to another with an eye towards finding new answers to the founding American questions of who we are, and why we are here.

I’m in! I can smell the newsprint already.

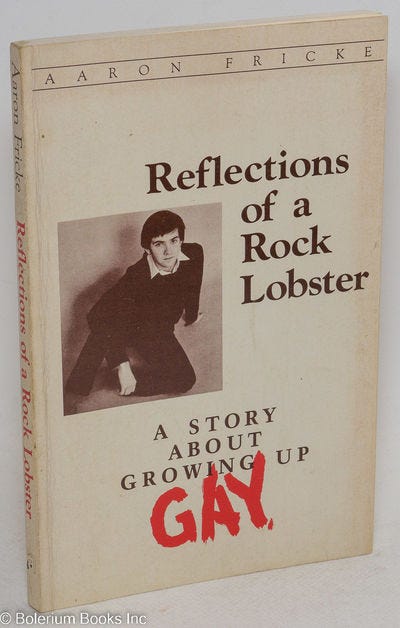

The weekend

And then, on Friday, Mrs. Oppenheimer and I left for two nights away in the Hudson River Valley—Beacon, Cold Spring, Hillsdale, Red Hook. We hit four bookstores but alas only one ice cream parlor. Picked up a number of great finds, including a Jane Gardam novel (third in the Old Filth trilogy) and this book, seen below, which apparently (I haven’t read it yet) is the memoir of a teenage boy who, in 1980, sued his Rhode Island high school for the right to take a male date to the prom. A chapter of gay history that I did not know. Can’t wait to read it: