“Ted Lasso,” “Shrinking,” Brett Goldstein, & the Power of Forgiveness

How a British Jewish comic became TV’s best theologian

In my line of work—writer, editor—I read thousands of words a day. I remember very little of what I read. One rare bit of writing that I do remember, and that I think about often, was a 2021 column in The Dispatch by David French, now a New York Times columnist, about the television show Ted Lasso and the power of forgiveness. For those sad souls who never watched Ted Lasso, which ran on Apple TV+ from 2020 to 2023, the basic idea is that a British football-club owner, recently divorced, wants to destroy the team because it was her ex-husband’s darling, which she got stuck with in the divorce.

To screw over the team, and thus her ex, she hires the least competent coach she can find: Ted Lasso (Jason Sudeikis), an American coach of American football (i.e., not soccer). This is a cruel thing to do to Ted, and when she grows to like him, she comes to regret setting him up to fail. French writes (spoiler alert!):

As Lasso’s fundamental decency relentlessly breaks down barriers and remakes his team, Rebecca realizes not just what she’s done, but who she’s done it too: a person she’s grown to love and respect. Lasso has become a friend, but it’s a friendship stained by a lie, and until that lie is exposed, the relationship can’t be real. So Rebecca knows she must confess. We, the viewers, brace for the moment.

I could link to the YouTube clip, but I won’t. [Here it is. —MO] It has to be seen in the context of the show, and when you see it in context, it smacks you in the face with its sincerity and power. Rebecca walks in and tells him what she’s done, in detail. With tears in her eyes, she walks through all her sins. She’s desperate to preserve their relationship, but he has to know what she’s done.

At that moment, her heart is completely in Lasso’s hands. In the era of “they’re waiting,” this is when they pounce—she deserves pain, and she’s going to receive pain. But something else happens. There’s a pregnant pause. He shakes his head. He stands up, and he simply says, “I forgive you.”

She’s stunned. “Why?”

“Divorce is hard,” he replies. “It makes folks do crazy things.” They embrace. That’s it. That’s the moment. Just like that, she’s forgiven. There’s no meltdown. There’s no rift between them. Lasso doesn’t punish Rebecca, not in the slightest. There’s no rom-com period of anger followed by tearful reconciliation. Lasso’s mercy is immediate.

I think about this essay all the time. When I first saw that moment on Ted Lasso, when Ted immediately forgives Rebecca, I broke down in tears. I don’t know that I could have said why. I probably would have said, “It’s just so moving to see one person being so kind to another.” Also, I cry at everything, so why not this? But French put his finger on what was going on, both on the show and inside me. He goes on to write, with a Christian spin that I don’t share but with an insight that I think is profound:

In fact it was the speed of Lasso’s response that was so profound. That’s when television art connected with divine reality. It reflected the character of God. His mercy is immediate. Even better, His forgiveness transforms our souls.

My former pastor was fond of describing the “upside-down” Kingdom of Heaven. In that kingdom, the last are first. In our weakness we are strong. If you try to keep your life, you’ll lose it. But if you lose your life, then you preserve it. Love your enemies. Bless those who persecute you.

This analysis increasingly applies to repentance and confession. In our diseased culture, the words “I’m sorry” often represent an end. They’re the end of your career, or your relationship, or your reputation. You can only survive if you push through, if you deny and spin and evade, and if you fight—especially if you strike back, hard, at your flawed enemy.

In the upside-down kingdom of God, however, the words “I’m sorry” represent a beginning. They bring a new birth. They renew and restore. Repentance is an expression of love. It shows regard for the person we’ve wronged. Forgiveness is an act of love. It’s a display of mercy and grace when a vulnerable person is in our power. Why did that moment in Ted Lasso hit so many of us so hard? Because, just for a moment we saw the world not as it is, but as it should be, and it was a far better world than the one we’ve made.

Interestingly, the vision of forgiveness seen in the show is, as I understand it, less the Christian one, in which forgiveness ultimately comes from God, than the Jewish one, in which God can only forgive sins against God—sins like Sabbath-breaking, eating un-kosher food, etc.—while for sins that man commits against man, forgiveness must be sought from man. If you offend another person, you don’t pray to God, and you don’t go to confession; in Judaism, you have to approach the person you wronged, and it’s up to him or her to forgive you. (More on this, from the Jewish sage Maimonides, here.) I have no idea how much Jewish education Ted Lasso writer/costar Brett Goldstein has, or if he was even involved in writing this particular scene, but perhaps something ancestral was at work in this particular dramatic set-up (or perhaps not).

I couldn’t help but think of French’s column, and Ted Lasso, when I saw a recent episode of another Apple TV+ comedy, Shrinking (another spoiler alert, for those who read on). This is a show about many things, including therapy culture and good-looking people having sex in beautiful houses, but it might fairly be summed up as a show about a man, played by Jason Segel, trying to hold himself and his teenaged daughter together after his wife is killed by a drunk driver. In the current, second season, the daughter, Alice, played brilliantly by Lukita Maxwell, gets to know the driver, Louis, who killed her mother; Louis is played by none other than Ted Lasso co-star and contributing writer Brett Goldstein. Soon after they meet, Alice visits Louis at his sad apartment, where he lives alone. He is clearly a broken man, crushed by the guilt he carries, and he seizes the chance to apologize to the daughter of the woman he killed. And—well, you really do have to go watch the whole series, right up until this moment, but suffice it to say she forgives him, in dialogue that could have been lifted from Ted Lasso.

“Shrinking” is a show about many things, including therapy culture and good-looking people having sex in beautiful houses.

(If you want to revisit the moment, watch this interview with Goldstein, interspersed with clips of the episode; the whole thing is lovely, but the payoff is at 2:20.)

In both shows, Ted Lasso and Shrinking, the offending party, the person being forgiven, is at first stunned: they can’t quite believe what has happened. They are so sure they will never be forgiven, indeed that they are unworthy of forgiveness, that they can’t understand what has happened. My first reaction was also one of incomprehension. The moment when Alice forgives Louis gets me every time. When I first saw it, I let out some sort of choked-up gasp (my wife looked at me to see if I was okay). I’ve watched a lot of TV, and this is one of my favorite TV moments. I will think of it on long car-rides and on slow dog-walks.

As French intuits, forgiveness has a bad odor right now. In the current moment, people are supposed to pay for their sins, real or imagined, forever. In postmodernity, there is no God to mete out forgiveness, and in the internet age, there is no human able to; sins like a wrong-headed tweet or a long-ago crime are seen as offenses against everyone, and when the crime is so diffuse, forgiveness is nobody’s job and within nobody’s power.

Also, forgiveness is relational, and thus at cross-purposes with wellness culture, which is fundamentally egoistic. This is the subject that Freddie deBoer took on a couple months back in his newsletter. His admirable fit of pique, titled “Selfishness and Therapy Culture,” was prompted by a Times column that questioned the value of forgiveness. DeBoer writes:

I’m only somewhat exaggerating or joking when I suggest that the piece argues that forgiveness is bad. It would be more accurate to say that it expresses an attitude generally skeptical of forgiveness as a concept, running to out-and-out antagonistic, speaking as though a virtue that people have embraced for thousands of years is some sort of con or dodge or scam. The charming headline reads “Sometimes, Forgiveness Is Overrated.” It’s part of the NYT’s Well vertical, which is to say, the self-helpy part of the paper that plays to the anxious and aspirational, a very important reader demographic. Writer Christina Caron reaches out to “the experts” to ask about the value of forgiveness and arrives at a conclusion that’s something like … eh. You see, the fundamental argument in the piece is that, because forgiveness only sometimes soothes the feelings of the forgiver, forgiveness is therefore overrated. Caron and those experts—what it could mean to be an expert in forgiveness, I have no idea—insist that the cultural directive to be forgiving is misguided, because it’s not always strictly speaking what’s best for the person who might forgive. That is the argument of Caron’s piece: that you should contemplate forgiveness only when and because it might benefit you. If it doesn’t, you should feel no pressure to forgive, let alone believe that you have an affirmative obligation to forgive.

Caron writes, “therapists, writers and scholars [are] questioning the conventional wisdom that it’s always better to forgive. In the process, they are redefining forgiveness, while also erasing the pressure to do it.” That is a constant, recurring theme of the whole therapy-as-culture genre, the notion that social pressure, the pressure to do something the individual doesn’t want to do, is inherently bad, inherently wicked. The notion that much of the difficult work of life is about working against our base individual desires, and the idea that we need to build social pressures to support this work, are both casually discarded as pathological. Better to feel no pressure to do anything, in pursuit of a self-actualized life. The directive to forgive is as old as human morality, but the wisdom of the past is of little concern compared to the impulse of the moment. Caron dismisses the opinion of Desmond Tutu, who resisted apartheid and risked his life in doing so and still emerged as a champion of forgiveness as the highest calling of human affairs. But what would such a man know, compared to the busy little strivers out there looking for even more permission to live only for themselves?

“Much has been written about why forgiveness is good for us,” Caron writes. “In many religions, it is considered a virtue. Some studies suggest that forgiveness has mental health benefits, helping to improve depression and anxiety. Other studies have found that forgiveness can lower stress, improve physical health and support sound sleep.”

This is all setting up a very big “but,” and it also establishes the terms under which Caron might consider forgiveness good or bad—with an actuarial table. This attitude is the nut of the whole thing, an attempt to justify or undermine transcendent human virtues with links to PubMed. That we might want to embrace moral virtues like forgiveness in the pursuit of benefits that can’t be measured with an Apple Watch goes unconsidered. The idea that there are higher virtues towards which we might labor is nowhere to be found. This passage’s implicit value system would justify saying that compassion is good because it reduces blood pressure, that honesty is good because speaking the truth causes a pleasant release of endorphins, that you shouldn’t rob and murder someone because doing so might worsen fine lines and wrinkles. It’s a stance on morality that has completely excised the interests of others, which is to say, an anti-morality, a consumer product marketed in moral terms, a justification for selfishness bought off the rack.

I don’t have to pile on poor Christina Caron of the Times; deBoer does that for us. (And in fact, Caron’s piece actually seems to insinuate that people who forgive are probably happier for it, in the end. One almost wonders if, in the process of reporting the piece, she turned against her original, contrarian premise, that forgiveness is overrated; and I wonder if an editor, smelling click-bait, forced her to stay the course.) But I do want to end with the thought that, as deBoer indicates, there are “benefits that can’t be measured with an Apple Watch.” To think of forgiveness as a matter of “wellness” is a huge category mistake.

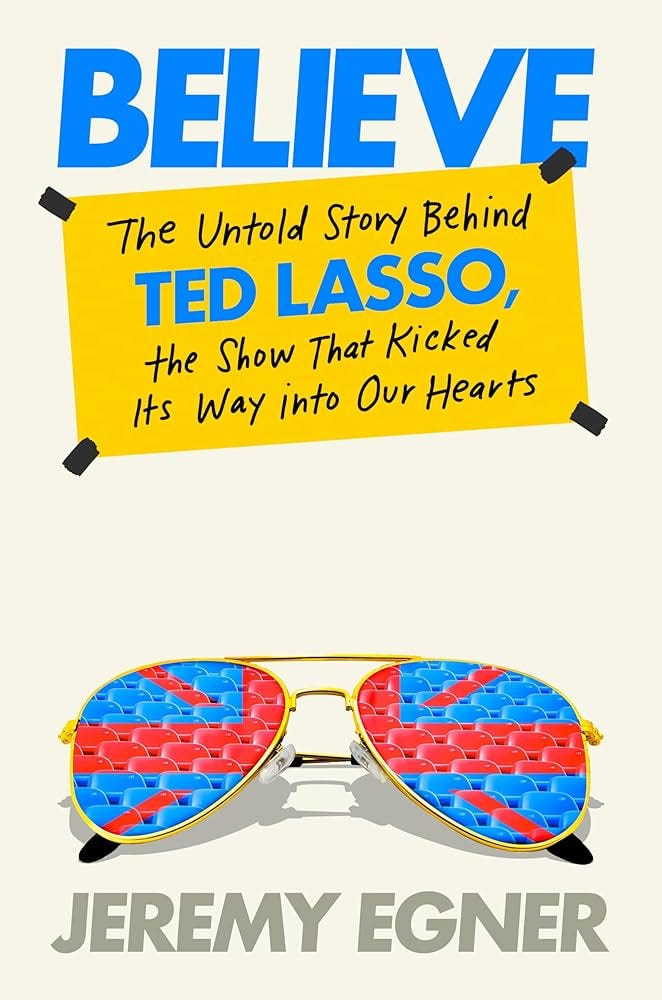

The benefits of forgiveness may be easiest to see through art—and nobody seems to get that more than Brett Goldstein, writer/star of Ted Lasso and Shrinking both. In the new oral history Believe: The Untold Story Behind Ted Lasso, the Show that Kicked Its Way into Our Hearts, by Times television editor Jeremy Egner, Brett Goldstein is quoted as saying, “You know what my favorite scene is, maybe? I’ve got loads. But it’s when Rebecca confesses to Ted. I was hidden in the room next to them, and I saw it from the run-through. I was just like, ‘Fucking hell, this is good stuff.’”

Fucking hell, I agree. In this Ted Lasso scene, as in Shrinking, the beauty of forgiveness lies in how the forgiver seizes the opportunity to give a gift, to lighten another’s burden—really, to free someone else from bondage. Maybe not everyone deserves that liberation, but then again, none of us deserves everything we have. Forgiveness is thus a gesture toward the universe, a way of passing on good fortune. It’s an act of thanksgiving.