Trump, The Gulf of Mexico, & Deadnames

The president steps into a philosophical debate about what a name is

President Trump’s record number of executive orders have met with outrage and, naturally, lawsuits. Ultimately, the courts will decide if Trump can deny citizenship to children born in the United States, or if he can withhold federal grants that have already been appropriated by Congress. But the courts can’t decide everything. Two of his executive orders—to rename the Gulf of Mexico and Mt. Denali—raise no clear legal issues, and have relatively low stakes, but are perfect illustrations of the limits of government, and the need for philosophy.

The question of what a body of water or a mountain is “named” is not really a question that government can answer. Unlike matters of citizenship, or the appropriation of funds, a name is not a matter of legislation or executive fiat. It’s much more than that. What exactly a name is is a matter philosophers have been quarreling about for over a century.

Analytic philosophers “would pretty much all agree that naming is more or less arbitrary convention, that there’s no essential connection between a thing and its name, and no linguistic fact of the matter as to what a thing’s name ought to be,” Thomas Bontly, a philosopher at the University of Connecticut, told me. “Linguistically speaking, ‘Saint Petersburg’ and ‘Leningrad’ are both perfectly good names for that city. The fact that ‘Leningrad’ has been discarded is important for historical and political reasons, but there’s no linguistic reason to say it was the wrong name and ‘Saint Petersburg’ right.”

The same logic would go for, say, Myanmar and Burma—the change was made in 1989 by the Burmese (or, rather, Myanmarese) government, for political reasons, and reflects no higher truth of naming. Our State Department still refers to “Burma,” for its own reasons. Both names win the assent of large numbers of people. Neither is wrong.

Yes, the government has power over how names appear on some official documents. But people or organizations choose whether to follow the government. Google made a choice last week to switch to “Gulf of America” instead of keeping “Gulf of Mexico” on Google Maps. But even there, matters are more complex: Google will continue to show “Golfo de México” to users in Mexico, and will show both names to those outside the U.S. and Mexico. In other words, most of the world will have a choice, to internally “choose” one name or the other, for the purposes of their own cognition.

But of course we all have a choice what to call anything. The gulf in question, for example, already has multiple names: Gulf of Mexico and Golfo de México, for starters. This multiplicity of names is old news to anyone who has traveled in Italia, España, or Algérie. We Anglophones are not “wrong” to call the countries Italy, Spain, and Algeria. But nor are the natives wrong in using native names.

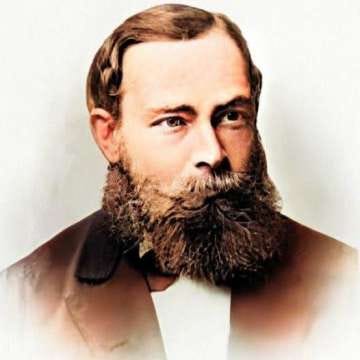

Philosophers of language divide, roughly, into two camps. The descriptivists, like the German philosopher Gottlob Frege (1848-1925), argued that a name picks out the cluster of associations people have with the name; the associations people have with “Mark Oppenheimer” (writer; born in Springfield, Mass., fan of English rock band The Heavy Heavy, lover of Triscuits) constitute the meaning of “Mark Oppenheimer.”

Later philosophers challenged that theory. For example, Saul Kripke argues that names are “rigid designators,” meaning that “Mark Oppenheimer” would still pick me out no matter what, in all possible worlds—like even if certain “known” facts about me, like my birth in Springfield, proved to be wrong.

Given these different ways of looking at names, one can better appreciate how contingent proper names are. For example, many trans people change their names when they transition to the other gender; their old name, or “deadname,” is treated as an incorrect name, a kind of mistaken name. The idea of the new name as being the “true” name has won wide assent, to the point that many obituaries of trans people now refrain from mentioning the deadname.

The philosopher Taylor Koles has noted, in a 2024 article, that the “use of rejected names to disrespect and derogate individuals is not unique to deadnaming in the trans community. Consider the community of African Americans and Afro-Caribbeans who have rejected their prior ‘slave names’ in light of their racial, religious, and political connotations.” Koles points to the case of Muhammad Ali, who rejected his birth name, Cassius Clay. “I didn’t choose it and I don’t want it,” Ali said.

For mapmakers like Google, there is a certain logic in deferring to government. To follow the government seems to be a political act, but to refuse to follow the government would seem like an even more political act. Trump has placed mapmakers in an impossible situation, but at least the first policy—going with government naming conventions—can be applied neutrally; it’s an easy, clear guideline.

But most of us aren’t mapmakers. We’re not doing the official naming, we’re just invited guests at the naming party. So we can ask, “What if the president threw a renaming and nobody came?” Individually, each of us can call a mountain in Alaska whatever we want. We can call that gulf next to Florida whatever we want to call it—Gulf of DeSantis, if you like. I, for one, will keep calling it the Gulf of Springfield. Who’s going to say I’m wrong?

Jascha Heifetz money

Every February 2, I am obligated to note that it’s the birthday of Jascha Heifetz, the greatest violinist ever. Last year, in this newsletter, I wrote:

Today is the birthday of Jascha Heifetz, perhaps the greatest violinist of all time. My grandfather Walter Kirschner, a lover of classical music, used to occasionally give me $10 in an envelope with a note that read, “In honor of Jascha Heifetz’s birthday.” He would do that even when it wasn’t Jascha Heifetz’s birthday. But today actually is Jascha Heifetz’s birthday, so I am going to give each of my children $10 of “Jascha Heifetz money,” as my siblings and I used to call it. I would be chuffed if you would do the same for a child in your life.

In high school, my insufferable English teacher (a recent Yale grad) insisted on calling Marcia Mar-see-ah even though she explained it was pronounced Marsha

Since then I have called folx whatever name they choose. We have so little we can absolutely claim as our own, not subject to others. One’s name should be among those things.

As someone with a relatively unique name (at least in the places I've lived most of my life, not where I was born) this is a topic near and dear to my heart.

1. For reasons, the first Gary I thought of upon seeing your naming of the philosopher was SpongeBob's pet/friend snail. But also, Gottlob is a freaking awesome name in and of itself.

2. The idea of Jascha Hefetz money is genius and only made better by the fact that it's also my sister's birthday.