Why do men argue about stuff they know nothing about?

In which I take up the challenge of a fellow Substacker to explain the male propensity for online quarrelsomeness

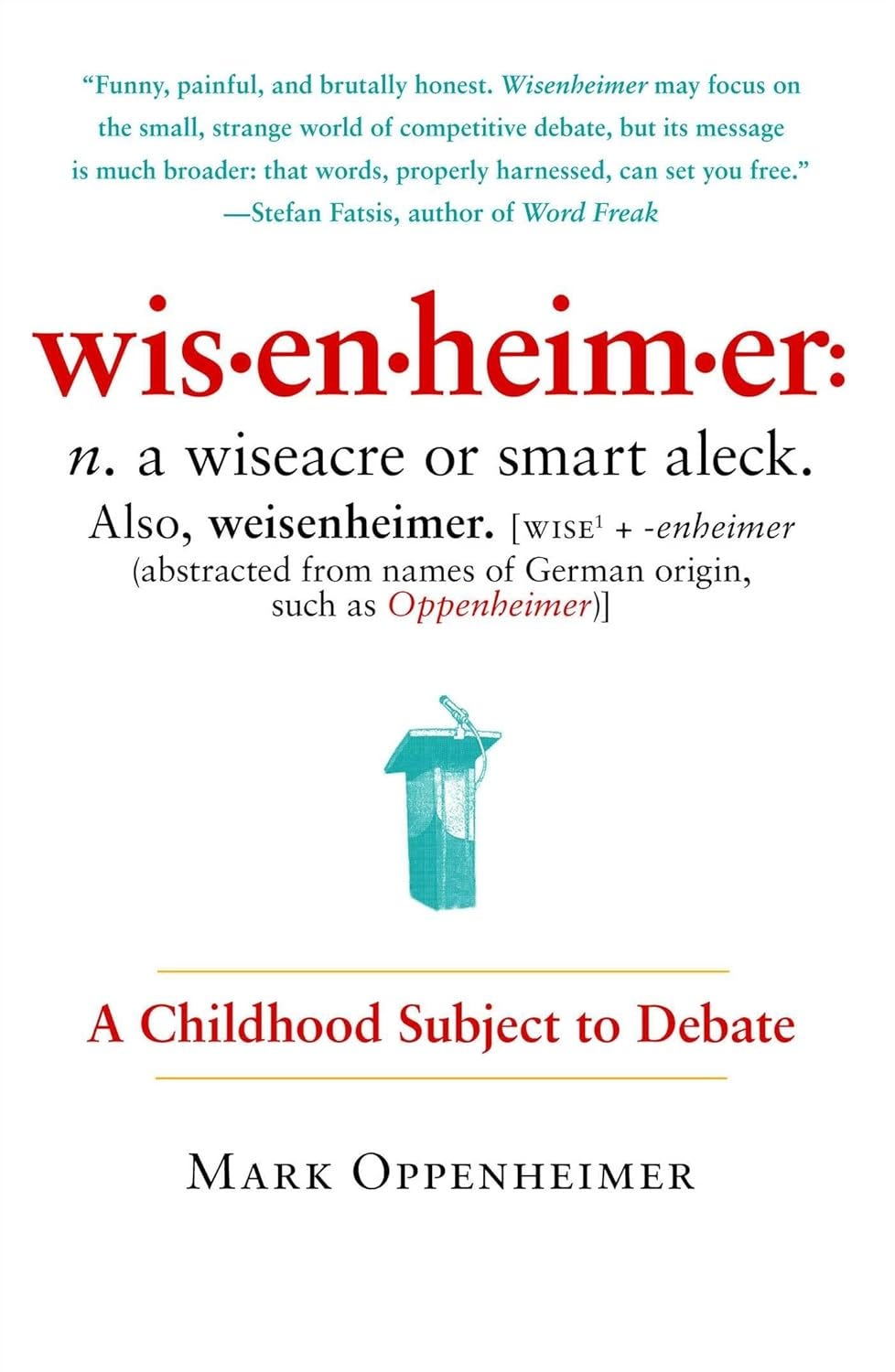

I am moved to respond to a post by the redoubtable Virginia Weaver, who recently wrote about whether sometimes men debate just for fun, even when they know they don’t know what they are talking about. It’s something I sort of wrote a book about—this memoir of my years as a high school debater, a book that most definitely should be optioned for an hour-long dramedy, Glee meets Rocket Science—and so I have a lot—a LOT—to say. And what I say also has to do with academic culture, feminism, Judaism, and Substack. Something for everyone. But first, here is what Virginia had to say, in part:

… I might be misinterpreting a type of social interaction a lot of men enjoy as malicious, and I would appreciate input if anyone wants to be generous with some. I’ll try to describe what I mean but it’s a bit amorphous. I’ve seen a few people vaguely mention that many men enjoy debating topics they don’t know much about, among themselves. Like, non-economists debating how to fix the entire US economy over beer, sort of thing. But it’s just a fun kind of convo for them, none of them thinks he’s actually the god of economics, and the rhetoric might be a little harsh toward others at the table but not meant sincerely as cruel.

I wonder if sometimes I interpret men doing this arguing-for-the-sake-of-it game in Substack comments as if they’re trying to have a serious (and not necessarily fun) intellectual argument, whereas the arguing is fun for them and that’s all [my emphasis, here and infra —MO]. Then I get annoyed, because I usually only feel like making a firm argument in a subject area that I know about. Arguing stresses me out! I only want to make a claim when the evidence outweighs my anxiety. I’m never playing a debating game, discussing a serious topic is a serious academic or confessional activity for me, even on my tiny blog. That means that someone who is just arguing for the sake of it while being unfamiliar with the topic at hand comes across to me as either arguing in bad faith or as a case of Dunning-Kruger. This happens often, but surely not so many men on Substack are bad-faith actors or whatevs, so I assume there’s a more positive explanation.

… And yes I’m sure some women enjoy that sort of debating, it’s just very very rare that I have these sorts of possible miscommunications with women. But many women know more men than I do so they can feel free to chime in too!

As so often happens in Substack world, there is a convergence of the forces, and two other relevant bits slid into my feed, totally randomly. Here is David Sessionsnoting that men like to argue (or maybe condescend to each other?):

And here is book critic becca rothfeld, in a somewhat older post, noting that philosophers famously enjoy what she calls “courteous disagreement” (side note: there is a whole genre of essays/post/etc in which philosophers wonder if one reason their field skews so male is because of the adversarial nature of philosophy talks and panels and conferences—discourteous disagreement—where the standard mode is to respond to a talk by ripping into the speaker, trying to destroy him (sometimes her) in front of the audience, and how this is treated as good fun, even though this kind of verbal combat often feels hostile to people who historically don’t have power in public spaces):

So this all adds up to an interesting launching pad for what I want to say, which is, Yes, Virginia, a lot of people, and especially a lot of males, really enjoy debate, even (or especially) when they don’t know what they are talking about; and what’s more, these people are often mystified to find that others don’t enjoy debate for the sake of debate, or to find that others can’t imagine that anyone does. That is, they sometimes find themselves genuinely surprised to learn that someone they engaged in a debate has come away with bruised feelings, because the exchange was legit fun for the first party, and it’s really hard to see how it was the opposite of fun for the other party.

Do I sound like I know what I’m talking about? I do. From about the ages of six to 33, my first criterion for any friendship was whether they enjoyed a good argument. And the more trivial the topic, the better. There is that cliché about how a certain kind of male bonding takes place via trivial debates, like “Beatles or Stones?”—like here:

—and while I never cared that much about that debate (I mean, Beatles, obvi), I have always enjoyed a conversation that revolved around a disagreement or a difference of opinion. By high school, I could happily debate affirmative action or the death penalty, but would also happily debate corduroy vs. denim (corduroy, obvi). When I discovered in junior high that debate was an actual activity, with trophies (!), I had the next six years of my life pretty well laid out for me. I won’t belabor this part of my history—if you care, please read the book!

—except to say that it was not about being mean to people or making them feel bad. It was not a negative expression, to debate someone, but a positive one. Making an argument and then hearing one in return was, for me, every bit as collaborative as it is for one musician to jam with another, or for two baseball players to have a great game of catch (or, if you want a slightly better metaphor, consider two players, a pitcher and a hitter, on the same team, practicing—one is trying to strike the other one out, and obviously that is adversarial, in a literal sense, but the enterprise as a whole is a chummy one, practiced by teammates who wish each other well; even a game against another high school, in which one wants to win, even smother the other team’s faces in the dirt, is ultimately a healthy practice, among people who should be happy to party together that weekend; certainly it should not put friendships at risk).

As a debate-minded kid gets older, he should, if he has decent social intelligence, realize that not everyone enjoys a lighthearted debate. For a long time, I understood this half-way but not entirely: I got that not everybody enjoyed a debate with high stakes (about affirmative action or immigrant rights), or which might be exceptionally personal (don’t argue with an adopted boy about the virtue of closed adoptions!), but I still couldn’t imagine that anyone could get bent out of a shape by an argument about Tiffany vs. Debbie Gibson (ask your Gen X friend, if you don’t get that). It seemed to me that if the stakes were really, really low, if the whole proposition was silly, then most anybody should realize that my picking a fight about it wasn’t an act of hostility, but of fun, even intimacy. Friendship-building.

Except, of course, many people don’t experience argument or conflict that way. Which does not make them better, or worse. It just is.

All of which raises a question about norms.

There are clearly different norms around debate in different communities. What is acceptable on a debate team is one thing, what’s acceptable in a trauma support group is definitely another. My sense is that the norms in philosophy, a historically happily contentious field, are changing. But the norms around argumentativeness are clearly more cultural than hardwired; there is more cross-cultural revulsion toward, say, theft or cuckoldry than there is toward argumentativeness.

My main interest is in arguing—yeah, arguing—that there is nothing inherently wrong with argument as a pastime, or argumentativeness as a benign norm, just as there is nothing inherently right about it. Those of us who enjoy argument need to recognize that there’s a time and a place, that not everyone shares our enjoyment of it—but by the same token, I’d like for people made uncomfortable by argument to allow that there are certain spaces where it’s an okay thing, maybe even a standard mode of developing or deepening connection and friendships.

One of those pro-argument spaces used to be the humanities academy. Or at least that’s my sense, maybe more from documentaries I have watched about the old Partisan Review crowd (and hence the Columbia and CUNY English departments in the the 1930s through ’60s) than from any actual historical research.

When I entered graduate school in religious studies in 1997, I figured that my fellow academics (professors, adjuncts, lecturers, grad students) would enjoy good-natured argument: to be clear, no name-calling, no demeaning people’s mothers, no hulking over people physically, Trump-style—but definitely permission to say to someone in a seminar, “I think that’s wrong,” or even a mild, “Maybe so, but what about [insert counter-argument here]?” And in fact, that was not how people talked—not in seminar. Every comment had to begin with, “That’s a great point, and just to build on that…” We were being trained as intellectuals, but there were clear limits on the point of view we could express, and the limits were set by whoever happened to have just spoken—because to say something that indicated that the prior speaker was simply wrong, or had reasoned poorly, was not really allowed.

When I got hired on at a university to teach, after getting my Ph.D., I figured maybe I’d find good-natured argument in the faculty lounge, or in faculty seminars.

Nope.

To be clear, these academics expressed disagreement, and not just with petty passive aggression. But when they did—as when they argued out their preferences about whom to hire in a job search—it was seen as an expression of enmity, or dysfunction. It meant things had broken down. Argument was never seen as a valuable, even fun mode of engagement.

Why?

Again, I have no idea why. That these spaces were no longer heavily male surely had something to do with it. But I think that misses the point. If there is a cultural mode that is being favored now, a mode that disparages argument, it’s not a female mode but a Gentile mode. Just as interrupting is more typical of Ashkenazi Jews in New York than of Lutherans in Minnesota (see the work of Deborah Tannen on “cooperative overlapping”), I think that favoring consensus, or amity, over truth, or honest disagreement (to be blunt about it), is culturally specific, too. And as the heavy proportion of Jews in humanities departments has declined, it’s not surprising that elbows-out argumentation has come into disfavor.

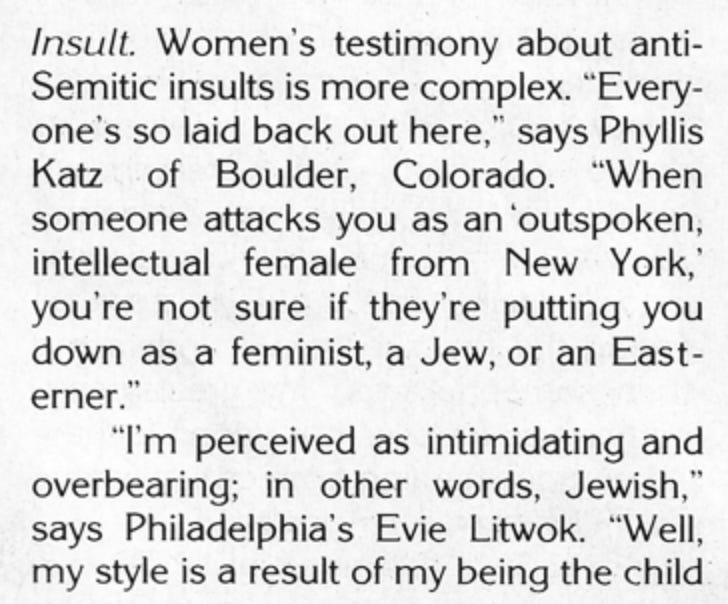

Here I’d like to refer to one of the classic essays of all time, “Anti-Semitism in the Women’s Movement,” written in Ms. in 1982 by (now-Substacker) Letty Cottin Pogrebin. Read the whole thing here. Here’s the important part:

So, to paraphrase Pogrebin, there is sisterhood, and then there is the ideal of (Quaker meetinghouse turn-taking) sisterhood. That is the ideal that has moved into progressive spaces, among all men and women alike. In that culture, interrupting has a reactionary cast. Quaker silence is good (and American); interruption or contentiousness is bad (and somehow ethnic).

And the opprobrium directed at interrupting, or loudly speaking one’s opinion, bleeds over even into disapproval of structured debates that actually, by their nature, offer everyone equal time, and into seminars where a teacher can referee things. Even if nobody is interrupting, the fact that there is argument is the problem. In the culture I am describing, argument is so unpleasant, so aggressive, so domineering.

I have tried this theory out on various academic peers of mine, and they agree with me, but usually in a somewhat bemused way; it doesn’t occur to them, having come up in academia in this era, that anyone would think there is something broken, or even just incomplete, about this model. One dean I spoke with—a major scholar, at a major university, a titan in her field actually—said to me, “You know, I do believe in disagreement, and in my articles, I often am criticized for viciously taking people down.” (Which is true; she is criticized that way.) “But that’s what the scholarship is for, what the books and articles are for.”

Basically, she was saying that you can tell people they are wrong, but not to their faces.

I think that is an accurate description of how many academics approach their guild: in books and articles, distinct schools of thoughts emerge, and some of them are really impatient with others. There is real disagreement, even real acrimony. But if you go to a conference—a humanities conference, anyway—and sit in on a panel or two or five, you won’t get the sense that there is vigorous disagreement. What you might get are people whispering to each other later, “Wow, I went to a really terrible panel. [So-and-so’s] paper was just terrible.”

To people’s faces, assent and affirmation; behind their backs, catty vitriol. What’s missing is the fruitful middle: polite but genuine disagreement.

I realize I have come pretty far from the original question I wanted to answer, which was whether some people argue just for the fun of it. The questioner, Virginia Weaver, was specifically interested in people who argue even when they don’t know what they are talking about. And that was a useful starting point, and yet I have ended up talking about the absence of argument among people who do know what they are talking about! (Such is Substack.) But the main point here is, yes, some people feel okay, even good, about argument.

That would have been a less surprising statement, I think, fifty years ago. Then certain norms began to change. Now we’re in a world where people—especially, I think, educated bourgeois people—see the argumentative mode, when it pops up, as a breakdown in culture. They are thus baffled by people who start or continue arguments apparently just for fun; and they are miffed by people who get argumentative even when the stakes are higher, or when they do know what they are talking about. Their heuristic is: argument=bad.

I don’t actually think that is what Virginia was implying; she seemed to think argument needed explanation only when it was low-stakes and ignorant, and she is presumably open to argument as a mode among knowledgable academics (for example). But I think the best way to get at that is to say, as I have, that you have to look at the place of argument in the culture.

Thoughts?

A very interesting subject! I think you could write several posts just about this. For example, go into the psychology of those, like you, who love arguing and like to find friends who like to argue. Decades ago a college friend of mine (side note, we were both goyish products of the Midwest) told me he had left an English PhD program in part because too many people there were, in his interesting and memorable phrase, "Talmudically disputatious". This subject also brings to my mind one of my favorite TV shows, Curb Your Enthusiasm. There have been plenty of very entertaining arguments in that show over the years.

I think the Talmud is full of argument for its own sake.